In the midst of Portland, Oregon’s “dumpster fire” chaos of 2020, two transient lovers met a quirky hustler offering a dream apartment deal. But it soon became a grisly nightmare.

It was 3:44 p.m. on June 16, 2020, when screams pierced the air, startling people at a nearby bottling company, a low-rent hotel and a trendy donut shop. Two young lovers came stumbling up the basement stairs of a dilapidated Portland fourplex apartment building with odd, runic symbols drawn on it — similar to the runes seen on a purple minibus that was often parked nearby. The couple had both been stabbed with a very large knife. The girlfriend, tiny at five-foot-one and 110 pounds, ran into the middle of the street, looked up at her neighbor, who had rushed out onto a balcony, and cried, “My boyfriend!” then collapsed.

The boyfriend, whose throat was cut and his heart, liver and lungs pierced, made it to the top of the basement stairs, then fell.

The neighbor on the balcony and others ran to help. People gathered. 911 calls poured in. But just before police arrived, a figure, later seen on the hotel’s video cameras, escaped via the rear of the building.

Three days later police arrested a man by tracking the purple minibus.

During a year in which homicides increased by 83 percent in Portland and made the biggest U.S. jump in six decades, this one grisly story might never have received much attention. But then a member of the far-right media noticed that five days before the stabbings, the alleged killer had been arrested at one of Portland’s chaotic late-night protests — which erupted in the wake of George Floyd’s killing in Minneapolis and grew into riots featuring clashes with law enforcement and counter-protesters.

“Breaking,” Andy Ngo tweeted to his then 668,200 followers. A man was arrested at a “violent #antifa protest,” but “quickly released,” then “stabbed two.” In September 2020, Breitbart, The Epoch Times, Law Enforcement Today, Daily Wire and others picked up Ngo’s outrage cry. The killings fit right into their attempts to link rising crime rates with protests and lenient law enforcement.

The true story, a deep-dive Narratively investigation reveals, is less political, and more bizarre. Six years earlier, the anarchist protester now charged with killing the young couple nearly won a seat in the Minnesota State Legislature — as a Republican. And the long, strange pandemic trip that led to this bloody scene was a product not just of political protest, but a national housing and homelessness crisis, untreated mental health issues and the inability of anyone in power to stop a self-proclaimed “insane pirate” who’d demonstrated violent warning signs again, and again, and again.

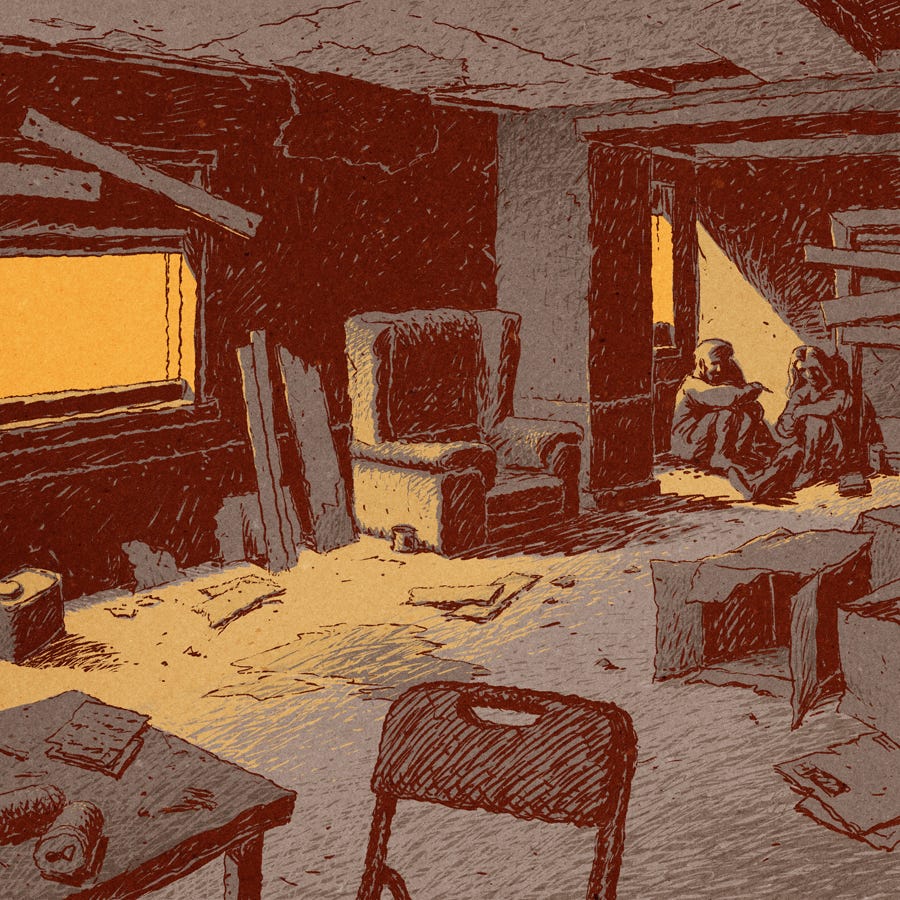

The faded blue-gray apartment building on Northeast Davis Street — two two-bedroom, one-bathroom units on each floor — is a housing microclimate, a graffitied eyesore surrounded by thriving businesses and pricey condos. A stately oak tree near the front porch whispers of better days. In recent years, the place became rundown, vacant, a haven for teenagers looking to smoke weed, locals say. City records show a pattern of code violations: water leaks, rodent infestations, rotting window frames and porches, plumbing line leaks, roof and wiring failures, trash, debris.

At some point, the fourplex became a magnet for unhoused people. Its owner, Lawrence Stover — a suburbanite who owned more than 15 Portland investment properties and, court records show, evicted tenants in at least nine of them over the years — was in his 70s. He either wouldn’t or couldn’t keep the place up.

In spring of 2020, a 38-year-old man named Phillip Lawrence Nelson arrived at the building. Nelson drove a unique purple minibus, with what appeared to be animal belts on the dashboard. He “just showed up one day,” recalls Bill Brandt, who lives in an adjacent building, “gained access to the building and started implementing repairs.”

“I found a dead house and I moved into it and I took it,” Nelson later told police.

These were days to remember. Local officials had just ordered everyone home as COVID-19 spread, shuttering government offices, homeless shelters and businesses. Nelson had spent much of the past few years bouncing around the country, joining protests in Washington, D.C., and the Dakotas, traveling to Montana before landing in Oregon. Photos of his minibus show it was outfitted with a bed, pillows and blankets, so he may have lived in it for spells

In early May, a man named Michael Johnson was working as a forklift driver at the bottling company across the street. Johnson is a father, grandfather and nonprofit leader, a Black man in his early 50s with a large frame and salt-and-pepper hair. He says he now preaches in an historic Black church but is also a former member of the Crips gang who’s “been through battlefields.”

Johnson noticed Nelson working on the fourplex’s water main. It was hard not to notice Nelson. He was six-foot-one, with pinkish skin, cobalt eyes, unkempt reddish-blond facial hair and a penchant for wearing long knives on his belt.

“Hey, you own this?” Johnson says he asked Nelson.

“Yeah, I own this, and I got two units that’s rentable,” Johnson says Nelson responded.

Johnson had been living in a Marriott Hotel downtown and was immediately interested. He soon moved in, with his girlfriend, teenage son and baby. He also alerted some co-workers, including Najaf “Nate” Hobbs.

Hobbs — 39, light-skinned with ice-blue eyes — had been in and out of prison for years after a challenging childhood, friends and family say, but was genial. He’d been living in his old black Mercedes-Benz, working, and using methamphetamine. He was looking for stable housing.

Cassy Leaton, a willowy 22-year-old with light-brown hair, blue eyes and an upturned nose, had recently come into his life. How they met is unclear, but like Hobbs, she had survived a rough upbringing, was using meth and had been living in a car.

Nelson’s offer was attractive. There was no deposit, no background check, no first or last month’s rent up front. Hobbs, Leaton and their roommate, Tyson Lee, moved in soon after.

“A job. An apartment. A pretty girl,” is how Nina Stafford summarizes the moment for her brother Nate. “He was getting his life back on track.”

“It was the most excited I’ve seen Nate in a long time,” his mother Debe Hobbs adds.

Cassy Leaton, who had just extricated herself from an abusive relationship, was also enthusiastic. “When she was with Nate, she was calmer, and laughed more,” her sister Brooke Leaton says.

For all its warts, the apartment was a roof over their head, some privacy, a place to stretch out, and — they hoped — a fresh start.

Nestled amongst the northern Minnesota headwaters of the Mississippi River, Bemidji is a beautiful, chilly small city. Like Coos Bay, Oregon, where Cassy Leaton grew up, it’s humble. “This is a poor area,” says Soren Sorensen, a local who knew Phillip Nelson, “kind of a hard-drinking town, where a lot of people have grievous injuries from doing things like logging.”

It’s a place where some government agencies’ call waiting features a recorded loon call, and people say “yaah” with a Midwestern drawl, like in the movie Fargo (or its TV spinoff, which is set in Bemidji).

Phillip Nelson graduated Bemidji High School, class of 2000. Images on social media of what appears to be the family home of his parents (who did not respond to a message) show bear and elk heads mounted over a stone fireplace, Bibles, antiques, support for Donald Trump. Nelson worked as an I.T. guy at the school after graduating, says Soren’s cousin Chris Sorensen.

From 2001 to 2005, Nelson served in the U.S. Coast Guard as an electronics technician and petty officer, third class. As a Coast Guardsman, Nelson wouldn’t have been deployed to Afghanistan or Iraq, but was awarded the National Defense Service Medal due to his active-duty service during the Global War on Terror. He won a Coast Guard Pistol Sharpshooter Ribbon and Good Conduct Medal before his honorable discharge for unspecified “hardship.”

After leaving the military, Nelson displayed troubling behaviors, both online and off. By 2012, Nelson’s Facebook page linked to the “White Trash Astronaut” blog, apparently penned by him, which features biblical quotes and cryptically angry posts, such as: “Beware the Babylonians. You think they care for you. You think they protect you. You think they know what is best for you. Only enough to keep you alive, only enough so that they can have large armies, only so they can have the best for themselves.” Chris Sorensen says Nelson struggled with a “diagnosed mental illness,” but he’s not sure which. In 2013 Nelson wrote on social media: “Professionals have told me that the best course of action for me is to get on disability. Make no mistake, I am climbing a mountain.”

During these years, those who knew him say Nelson sought to “indigenize,” wandering the woods and trails around northern Minnesota lakes, foraging, mushroom hunting, practicing archery and making pine-needle tea.

“He tried to make a living for a while doing things like making medicinal deer fat” and “bad taxidermy,” adds Soren Sorensen, who described Nelson’s avocation as “weird modern alchemist.” Nelson posted one graphic photo of a freshly skinned animal to social media. “Jesus Christ, dude,” a friend responded. “Rabbit?” asked another. Next to an image of scrap leather, Nelson wrote, “Blessed with hundreds of square feet of leather and a great sewing machine.”

It may have been a retreat or coping mechanism, but it was also a passion, and a choice. “Phil definitely chose this lifestyle in the swamps and riverbanks,” Soren Sorensen says. “He’s got siblings who drive nice cars, who live in nice houses.”

At some point, Nelson got married and had kids. The timing and details aren’t clear. A Bemidji address included in public records shows a modest one-story wooden cottage on a corner lot, surrounded by trees, a fenced-in backyard.

According to Soren Sorensen, Nelson also became “involved in organized Republican politics in our area.” Sorensen, who has himself been a candidate for Minnesota elected office with the Democratic-Farmer-Labor party, says “the local GOP go for some pretty wild characters.” (A Politico story from a few years later described the Minnesota Republican party as “in ruins.”) Sorenson says Nelson “was embraced by those folks, went to parades with them, and he caucused for Marco Rubio.” In 2014, the Bemidji Pioneer reported Nelson was “recruited” by Minnesota Republicans “for his first-ever race to try to take down [Democrat John] Persell,” a three-term incumbent in the state House of Representatives.”

A blurry, low-resolution selfie on Nelson’s Facebook page from July 4, 2014, is titled: “That one time, on the campaign trail.” It shows Nelson in a blue collared shirt and wraparound sunglasses on a flatbed trailer with six people behind him, American flags everywhere.

Nelson’s performance in the race against Persell was decidedly unorthodox.

“I have no idea what I’m doing here,” he said in a debate televised by Lakeland PBS. He wore gelled hair, an earring, a pink tie and a creased button-down under a fleece vest with a fuzzy collar. He touted “squeezing” oil companies “for all they’re worth.” During another debate, he pulled out a knife and “displayed it to the audience,” the Pioneer noted. “This is my right to bear arms,” he announced. “I’m really okay with anybody having any kind of weapon they want on their person.”

Nelson lost the race while winning 45 percent of the vote, or 6,385 votes. His political activism continued — but not along traditional G.O.P. lines.

In 2016, Nelson traveled to join the Standing Rock protests, a major climate change and water rights battle fought by the Standing Rock Sioux against construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline. Nelson was interviewed by a TV station while constructing what he called a “water filtration building.” That a former Republican candidate would join a progressive environmental cause suggests Nelson’s politics had changed, or never translated to the usual left-right boxes.

In 2017 and 2018, Nelson was frequently in trouble with the law for domestic violence involving his wife and children. In two of five Beltrami County booking photos, Nelson smirks. “Male took computer and cell and threw the female out of her car,” a Bemidji police report says. “She is 3 months pregnant.” One child told the officer: “Mom and Dad got in fight. Daddy got really really angry. He took mommy’s phone. Both mom and dad were yelling. Mom told her to go out of the window.” Another explained that “The[y] were hiding down stairs [when] Mom told them to go outside. Her dad pushed her mom down outside. That made her cry.”

Nelson’s wife “was so scared,” a Bemidji Police Department report states, “that she instructed her two daughters that were at the residence to jump out of the window and run to safety.” Then she grabbed her one-year-old son and fled.

Five officers responded to one 2017 incident, in which an officer documented “foot tracks in the fresh snow” near Nelson’s wife’s home and wrote that Nelson “just recently posted a photo on his facebook page of himself pointing a gun with the caption ‘happy mother’s day.’”

“It appears that Phillip Nelson’s behavior is getting worse,” the officer concluded.

His wife thought Nelson “would harm her” and, Chris Sorensen says, she and Nelson were eventually divorced. Nelson was court-mandated to complete a “Batterer’s Intervention Program,” but Minnesota Department of Corrections officials say he didn’t complete it, choosing to serve time in jail rather than comply with probation. He spent 61 days in jail for five arrests for misdemeanor fifth-degree Domestic Assault and repeated violations of No Contact Orders.

On April 27, 2017, as Bemidji police searched for him, Nelson reportedly took off for a protest in Washington, D.C., likely the People’s Climate March, which took place two days later.

It’s not clear what Nelson did in 2019 or 2020 before his apotheosis in pandemic Portland. His Facebook posts suggests he went camping in Montana, hung out with a female friend and obtained a large “Jungle survival knife from Argentina.” He may also have been practicing another unusual gig, which he later brought to Portland: takeovers of vacant buildings. He would later testify in court: “This is stuff that I’ve practiced in more states than Oregon. I’ve been doing this successfully in Minnesota and Montana, without any issues.”

By 2020 he told Portland police he’d “been out meandering around for the last three years or so,” and “registered at the [Veterans Administration]” when he got to Oregon, but “Covid put a dent in our normal meetings and everything.” In Portland, he met a girlfriend, and developed a cannabis habit. “I need pot,” Nelson wrote on Facebook on April 15. “Unfiltered life is a bad drug that wreaks havoc on my mind and kills my productivity.”

Despite his own indulgences, or coping strategies — Nelson also appears to have been growing “psilocybin mushrooms” in his unit at the fourplex, which Portland Police Detective Rico Beniga later testified were “labeled” in half a dozen “plastic totes” of unknown size, possibly as preparation for distribution or sale — Nelson viewed people who used meth as dangerous lowlifes. That same day, Nelson wrote, “People on meth will smile at you and say all the nicest, kind, polite things. They do this … So that you will let your guard down and let them close. THAT’S when they stab you. … I let people close a few times, after that its straight to my get the fuck out of my face.”

Nate Hobbs’s full first name, Najaf, could be a reference to a military training area near Corvallis, Oregon, or a city of a million people in Iraq, home to a holy Muslim site. His mother, Debe Hobbs, won’t name or talk about her ex-husband, Nate’s father, with whom she is no longer in contact. She says he physically abused her, throwing her down the stairs when she was pregnant with another child.

There were good times, too. Nate grew up in Gresham, a suburban city of 113,000 people east of Portland, and lived in the same house since age six. He had a Radio Flyer-style red wagon, rode BMX bicycles, loved Kurt Cobain, ate pizza on Friday nights. He named the family’s cat Pizza. “He just was always a clown,” his sister, Nina Stafford, chuckles. One night Pizza got out, and Nate walked all around the neighborhood in the dark, looking for the all-black cat, yelling, “Piiizzzzaaa!”

An empathetic kid, Nate was close to his six siblings. He and his brother (and fellow Cub Scout) Sharaf “brought home stray kids,” his mom recalls. Nate “would just like bring home friends, and I would be like, ‘Well, does your friend have a home? Your friend’s been here a couple days, do you think they can go home?’” When Nate would ask for clothes, he might give them away to kids that didn’t have any. “He was never a material guy,” his mom says. “His gold was in his heart.”

But Debe Hobbs says her husband didn’t only abuse her; he also hurt his son Nate. “Something happened,” she says, “and I don’t know to what degree. We were divorced shortly after that.” Nate went through therapy and would “freak out whenever [his dad] came around.”

Starting at about age 14, his mom recalls, Nate struggled with his mental health. He tried to take his own life on at least one occasion, his mom recalls, and was “in and out of psych wards,” but mental health providers “never really gave us a diagnosis.” Nate was a passenger in a car accident when he “went through the windshield” of a stolen vehicle, which likely caused head trauma and led to juvenile detention.

Nate eventually became addicted to meth. A friend named Maurice Artiago, who worked with him at Portland Bottling Company, says Nate’s addiction impelled him to become a “copper bandit,” when he wasn’t working, or incarcerated. An ex-girlfriend named Rhonda Durant recalls Nate would go get publicly available lists of buildings scheduled to be demolished so he could scavenge unused metals. “I mean, this man did his research,” she says.

Despite the apparent long-term addiction, everyone I spoke with remembers Nate as kind: “That man would give you the shirt off his back,” Artiago says. “He was my bro bro.”

Cassy, or Cassandra, is said to mean “thorny tree.” For Cassy Leaton, some thorns grew early.

Cassy’s mom, Nynette Leaton, says Cassy was in the Intensive Care Unit for three days after her 1997 Detroit, Michigan, birth. She also had colic. “As we’re leaving the hospital,” she told me, “the nurses were literally shoving a binky in her mouth, saying, ‘Good luck with this one.’”

After the family moved to Coos Bay, Oregon, at the tender age of 18 months, Nynette Leaton recalls, Cassy ran onto a shingled well cover so sun-broiled that it “melted all the skin off” the bottoms of her tiny feet. The damage caused even ER nurses to weep, she remembers.

Her home life was rough, and reached a turning point, Cassy’s grandfather Randy Leaton says, when Cassy and her sister Brooke were three years old and 18 months, respectively.

“I walked in their house one day,” he says, and “there was cat manure all over the house and … busted glass all over the floor, a mirror on the table with a razor blade on it. The house just looked like a tornado went through there. They had the girls in the bedroom and … there was cat shit on the floor. I turned them in. The state walked in there, and it still looked just like it did when I was there. So, they took the girls and brought them to us the next day.”

Randy Leaton says Cassy had a happy life after moving in with him and her grandmother. The couple worked as a pharmaceutical tech and custodian. They weren’t rich, but Cassy and her little sister “had dogs and cats, they had everything that other kids had.”

“The thing I remember the most was camping trips and things like that,” he says. “We would go up the river and the girls would swim,” camp and roast hot dogs. Cassy loved the water, he adds.

By her teenage years, though, Cassy had spent time in institutions and juvenile systems. A selfie from that time shows a swollen lip, a hard expression, a bar over a window. In a 2015 letter her mother shared, a teenage Cassy writes, in pencil, “I can’t wait to get outta here, mom. I get bored all the time.” She writes of not being able to take her pencil to her room, of a relapse, and a breakup with a girlfriend.

Cassy and Nate weren’t angels, nor just victims. But a search of local court records paints a picture of two nonviolent repeat offenders who incurred the kinds of offenses that often accompany drug addiction and vehicle residency. Najaf Hobbs’s name was attached to 71 charges, including felony drug possession, felony burglary 2 and forgery, as well as a litany of minor crimes like “misuse of bicycle,” “littering” and “violation of bicycle equipment requirements.”

Though 17 years younger than Hobbs, Cassy Leaton seems to have been on a similar trajectory. Court records show 32 charges for her, all misdemeanors or parking violations, or speeding tickets.

The circumstances of Nate and Cassy’s first meeting aren’t clear, but Leaton had recently fled an abusive relationship. According to news reports, on March 31, 2020, her ex-boyfriend fled from, then crashed into police vehicles and was booked on “elude by vehicle, hit-and-run, reckless driving, meth distribution, heroin possession, felon in possession of a firearm, and domestic violence.” Cassy Leaton appears to have been the person attacked in the domestic violence charge.

Her aunt Amber Antu remembers the man coming to her house for Cassy. “He scared me,” she says. “He put a gun to [Cassy’s] head, she told me. She took her bag, she ran for her life.”

Nate and Cassy thought they got a huge break, finally, in May 2020 when they met Phillip Nelson and got a deal on a rental apartment that seemed too good to be true.

Nynette Leaton recalls Cassy “called me excited, because she was signing her first lease!” Rhonda Durant separately recalled Nate’s exhilaration: “‘I got a place, I got this place, you’re not going to believe it, I’m so excited!’”

Nelson apparently charged $1,200 a month to Michael Johnson for his apartment, and another $1,200 to Hobbs, Leaton and their roommate Tyson Lee, who knew them from the warehouse across the street. (Lee, then 31, could not be reached for this story; homicide detectives did interview him.)

Nelson was “basically scamming various people,” prosecutor Ryan Davidson later asserted, and “keeping that money.”

According to the police, owner Lawrence Stover was aware Nelson was staying in the building but had not given him permission to rent the apartments and accept thousands of dollars.

In Nelson’s bail hearing, Detective Rico Beniga stated: “I interviewed Mr. Stover over the phone and determined he was the actual building owner, through county records. He told me that he was aware that a subject named Phil was residing in the building, and that he allowed him to stay in the building. He wasn’t paying rent, but Phil was sort of managing the previous problems he’d had with what he termed ‘vagrants’ — kids entering and damaging the building. He did say, however that Phil did not have authority to sublet [or] collect rent, and if he did so, he was not aware of that.”

The Minnesotan seems to have carried out his “vagrant management” activities zealously. On April 30, 2020, Nelson posted on Facebook, “How to drive out tweaking drug dealers from your neighborhood like a Godfather.” One: “Don’t be calm.” Two: “Disrupt/disturb.” Three: “Leave a dead animal on their bed.” “I didn’t have a horse’s head,” he adds, “so I used the squirrel who got splatted.”

Nelson’s signature at the bottom of Michael Johnson’s lease includes a strange symbol that Henrik Williams, a professor at Sweden’s Uppsala University and an expert in Nordic runes, says combines a “P” and an “N,” of the older futhark type. It’s the same symbol painted on the back door of the unit Nelson moved into. The runes on Nelson’s purple minibus, Williams wrote in an email to me, read “Herkamer.” What that meant to Nelson is anyone’s guess. It may be a reference to the “Herkimer” diamond, which is softer than a regular diamond but hard enough to scratch glass, or Nicholas Herkimer, a martyred, slave-owning, Mohawk-speaking Revolutionary War general who died from his battlefield injuries.

Weird as his candidacy for Minnesota elected office was, Nelson was even more unorthodox in cosplaying Portland apartment manager. He “always” wore a large knife in a sheath on his belt, Johnson says. Hobbs’s friend Artiago clarifies that it was “half[way] between a sword and a knife.” Johnson came to see Nelson as “past the Portland weird stage, more weird as in creepy.”

Yet for the folks living upstairs from him, the decision to trust and give money to Nelson was simple pragmatism: two-bedroom apartments in this close-in neighborhood go for twice what Nelson asked, require big down payments, background and credit checks — any of which could have been a deal-breaker for Hobbs or Leaton.

On May 10 or soon thereafter, the couple was in, and over the moon.

Hobbs had been talking about getting sober, friends and family say. “He was doing good,” Artiago says. “I was proud of my homie; he wanted to do big things this time.”

It was Cassy Leaton who first heard from a neighbor that Nelson wasn’t who he claimed to be. “This was devastating to Nate and Cassy and they immediately researched, found the owner, called him and left a message,” says Hobbs’s sister Nina Stafford. “Four days before Nate died, he said the owner never called back. I think they left a couple messages.”

All the upstairs residents stopped paying Nelson. In Johnson’s words, “the weirdness started coming to truth — like, ‘Uh oh.’”

Around this time, Johnson and Nelson had a heated confrontation about the money. Johnson later tells police that Nelson told him, “Mike, remember, I need you to do two things: laugh, and [know that] I’m an insane pirate.”

“My response to him,” Johnson says, “was, ‘Hey, I’m a pirate, too, then. Because you’re not going to keep taking my money, buddy.’”

Nelson referred to himself as a “pirate” more than once. “His favorite quote to me,” Johnson says, “was, ‘I’m a pirate, and pirate laws are different from the land laws.” Artiago recalls Hobbs saying of Nelson, “This stupid motherfucker said that he was a pirate, that he goes from town to town, and he fixes up old apartments and he rents them out to veterans.” Separating fact from fiction, boasting or gossip is tough here. But for Nelson, the “piracy” theme may have been a clue to how he saw his caper: taking up residence in a vacant or abandoned building, fixing it up a bit, putting on new locks, “managing” it, finding vulnerable renters, getting paid.

In October 2021, Nelson told a Multnomah County court, “This is stuff that I’ve practiced … successfully … without any issues.” Johnson says Nelson told him “he had another squatter house somewhere that he was working on.”

Nelson even put up his shingle to advertise on the fourplex, like a property management company might, his name and address written out in purple above his strange runic signature.

In mid-May 2020, Johnson says, he, Hobbs and Leaton told Nelson, “Hey, we’re not giving you no more money,” to which Nelson responded, “Well, I’m going to burn it down then.” For Johnson, who had a girlfriend and two children with him, the threat took things “to a whole other level.”

On May 20 at 6:30 p.m., Johnson called the police to report fraud. (Someone else, possibly Tyson Lee, also called police.) Officers Zachary Nell and Dave Browning arrived at the fourplex at 7:06 p.m., their dashcam video camera recording. The transcript of the next 51 minutes suggests just how contentious the situation at the fourplex had grown.

The officers first spoke to Johnson. “So, we’ve been having a conversation about getting our money back,” Johnson told them. “And [Nelson’s] like quoting all these different laws and scriptures about squatters can do this and squatters can do that.”

The officers also interviewed Nelson, Hobbs and Lee.

“Well, I’ve unfortunately got some renters that are wanting to not pay rent,” Nelson told them. “This is my house,” he added. “The law requires me to say that this is ‘my house.’ … It’s [called] adverse possession … ‘squatters’ rights.’” He told the officers that an Oregon law, Acquiring Title by Adverse Possession, makes the building his. (It’s a far-fetched claim that’s common currency in homeless camps; I heard it before while reporting another story for Narratively.)

“At the end of the day, we have a nationwide housing crisis, right?” he told the officers. “We’ve got 16 million houses that are essentially going empty.” Nelson described the fourplex as a “rotten piece of shit,” a “trap house” and “crack house” and proclaimed, “I picked up a piece of illegal garbage and I made it into something legal and usable.”

Even before talking to Nelson, the officers seemed to worry about the legal complexities of the situation they’d just walked into. “It’s a big report,” Officer Browning said. “We might just have to do a lot of documentation about this,” Officer Nell responds. The Oregon statutes aren’t clear on these things, Browning says to Johnson and Nell. “Good luck with case law on that one.”

Eventually, as the officers kept questioning his claims, Nelson grew angry and argumentative, saying Johnson “doesn’t understand how capitalism works,” calling Hobbs and Lee “fucking tweakers” and adding nonsensical folklore like, “Have you heard that theory, that if I wax that van, I could take it?”

“I don’t touch nothing unless it’s just trash and garbage,” Nelson added. “I literally live my life by picking up — everything I have is donations.”

Eventually, the officers made it clear to Nelson that they weren’t buying his theories. “I’m going to go ahead and say that you don’t have this property by adverse possession, because Oregon law right here says that you have to be — maintain actual possession of the property for a period of 10 years,” Browning tells Nelson. “You’ve only been here a week or two. … You’re about nine and three-quarters [years] short of owning it,” he told Nelson. “Case closed.”

Nelson got “jacked up,” in Officer Nell’s words, and the officers told him to calm down. “I’m not going to calm down,” he responded. “It’s fine. My game’s up.”

Nelson repeatedly swore at the officers and admitted to threatening to burn the house down. Yet he was not arrested or cited. The officers called owner Lawrence Stover during the visit but did not reach him. Before leaving, they discuss with Johnson whether or not the case would be civil or criminal, and tell him that will be a District Attorney’s decision. And they ask about Nelson’s vehicle, and he points the officers to “the purple camper” parked on the side of the fourplex.

“Interesting,” Officer Nell says. “That’s a unique van.” His partner responds, “Yep.”

In his narrative of the incident, dated at 10:40 p.m. that night, Officer Nell writes that he informed all parties that he would refer the case to the District Attorney for review. It’s not clear if or when that happened, or if the D.A.’s office took any action as a result. A Portland Police report dated the next day, May 21, describes its “Internal Status” as “Not a Criminal Offense.”

Days later, as he once did in Bemidji, Nelson left his problems behind and headed to a protest.

By this time, Nelson’s Facebook posts suggest, the onetime Republican candidate had fully shape-shifted into an anarchist radical.

Portland’s demonstrations, which would eventually number more than 100 consecutive days, started in late May. On May 30, as violence flared up, Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler declared a state of emergency and a curfew.

On June 1, Nelson posted, “I just got disowned by my father.”

On June 3, the night after “Tear Gas Tuesday,” Nelson wrote his friend Chris Sorensen that “the cops gave the coolest photo OP. Me in my costume being the last one running out of the CS gas cloud holding my hat to my head. The photos from this are going to be Epic as Fuck bro!” A new profile photo on his Facebook page showed him in a black medieval plague doctor mask he seems to have made himself. “I like this cat and mouse game,” Nelson wrote his friend. “Its fun.”

Was Nelson really an anarchist? A Black Lives Matter supporter? Or was his participation performative, an adrenaline rush, a social dynamic in an age of isolation?

“There’s just a part of him that’s drawn more to chaos or trouble than any agenda or ideology,” says Soren Sorensen, who says the Nelson he knew, far from a radical leftist, may have been ideologically “Christian nationalist.” His Facebook feed includes a photo of a spray-painted swastika, although most of his posts focus on his many interests, including the outdoors and politics, not race.

Some at the fourplex thought Nelson’s true motivation for protesting was social. “We thought his only purpose down there was the girlfriend,” Johnson says.

At 11:45 p.m. on June 11th Nelson was arrested downtown for “Interfering With a Police Officer,” a misdemeanor. He was booked at 1:02 a.m. on June 12, then released, like a thousand others, his charge the same as that used against three-fourths of those arrested. Multnomah County District Attorney Mike Schmidt’s office adopted a policy of catch-and-release for most protesters, prioritizing holding only those caught “breaking windows of businesses, lighting things on fire, stealing.”

On Friday June 12, the day of Nelson’s release, Nina Stafford saw the fourplex for the first time and her brother Nate for the last time.

“He couldn’t get his checks cashed, because he didn’t have current ID because of COVID” office closures, she recalls. He called his sister “and asked me if I would help him cash his checks.” They went to the bank. When they got back to the fourplex, Hobbs worked on the tire of his Mercedes, then Leaton pulled in with burritos from Don Pedro’s. “It was the first time I got to meet her, so that was pretty cool … I sat at the table and talked to Cassy and … we just had a brief, ‘Hey, how are you? How do you like the new place?’ thing.”

Their new home was “dilapidated,” Stafford remembers. “Water spots on the ceilings, and ratty carpet. Probably a ton of cockroaches.” Yet Hobbs loved the front porch, the oak tree. “He told me he wanted to build a tree house in there.”

Stafford isn’t sure if her brother was sober or not. (Toxicology reports for Hobbs, Leaton and Nelson were not yet available at the bail hearing.)

At some point in the following days, Nate Hobbs changed the locks to his apartment. “Nelson was upset with Nate because” of that, Detective Beniga later testified. Around noon on June 16, Beniga testified, Tyson Lee, the roommate, saw Nelson. He “was apparently upset, flipping Mr. Lee off, and when Mr. Lee asked Mr. Nelson what that was about, he said it was something between him and Nate.”

At about 2 p.m. June 16, the day of the murders, a Gatorade bottle filled with something was placed outside Nelson’s door. In a photo Nelson posted to Facebook, it looks like the bottle contains crumpled aluminum foil on top of a bluish liquid. Johnson told me Hobbs put it there, and that it was a “bomb … in a water bottle.”

It’s possible the bottle was what the CDC calls a “homemade chemical,” “acid” or “MacGyver” bomb. These things can be viewed as middle-school science experiments — as Max Imagination does — but they’ve also been seen as serious crimes meriting prison sentences of 18 years.

“It’s a common prank, but it’s a felony,” Lakeland, Florida, police spokesman Sgt. Gary Gross explains, in The Lakeland Ledger. “It’s an explosive device.” Judging by news reports, such devices rarely result in serious injuries, much less fatalities. In any case, Johnson adds that “I guess [Hobbs] took it back, and then, just dismantled it,” possibly after an argument with one of his roommates. The bottle and its contents weren’t found by police during their search of the premises, and Detective Beniga testified that he couldn’t tell what it was from the photograph.

Nelson saw a bomb, and a threat.

“Look at these fucking retards!!” Nelson wrote on Facebook. “They put a chemical bomb outside my door. The fact they are complete morons and don’t actually know how to do it right doesn’t remove the legal fact from them that this counts as an attempt on my life. Oops. I like the term Causus Belli.” (Casus belli means a cause or provocation for war.) There is no indication Nelson reported the “bomb” to police.

Nelson had recently turned off the water to the upstairs, something he’d done before, Tyson Lee told Detective Beniga. Perhaps Nelson thought the lack of water would force the others to pay up or move out.

But Nate Hobbs loved a shower (He was “always super clean,” his mother recalls, even when he was homeless.) And he had a Sawzall.

Tuesday, June 16, 2020, was his day off. Tyson Lee wasn’t around at the time, Johnson says. Hobbs “woke up, and he couldn’t take a shower,” Johnson recalls. “So [Hobbs] had a little hand-held saw. And I guess his girl was eating some noodles or something. And he came down…”

The following is a preliminary account of events at the Davis fourplex beginning at 3:31 p.m. on June 16, 2020, described by police in Nelson’s bail hearing (based in part on video from the hotel), a prosecutor’s memo and my interview with Johnson.

At 3:31 p.m., Nate Hobbs arrives at the fourplex in his black Mercedes. Cassy Leaton pulls up soon after in her white Ford Focus. They both go up to their apartment at 3:33 p.m.

At 3:36 p.m. Hobbs exits and goes down toward the basement, where the water control to the building is located, using the small concrete staircase on the east side, Leaton following.

Around 3:40 p.m., the pair emerge from the basement staircase and return to their unit. At 3:41 p.m., Hobbs goes back down, followed by Leaton. He brings a light-colored Sawzall, which he uses to cut a “center wood panel” out of the exterior basement door to gain access to the water.

Upstairs, Johnson and his teenage son are playing Call of Duty Warzone, when they hear “this banging, like boom-boom-boom, boom-boom-boom-boom!”

Then “screaming,” Johnson says. At 3:44 p.m., the video camera captures Leaton running out of the basement onto Davis Street, stumbling and shouting for help.

“She was ‘Help, Help!’ screaming ‘Help,’” Johnson says. He goes out onto his upper front porch and sees her “screaming [while] she was going across the street. … My jaw had to have been hanging out.”

Detective Beniga says Leaton was “running around in the street, asking repeatedly for help.” From the street, Johnson said, she looked up at him, standing on the balcony. “Then she says, ‘My boyfriend!’ And then she drops.” Leaton falls to the ground and curls into a fetal position.

“So that’s when I start to take off.” Johnson runs downstairs, outside, and calls 911. Other people begin arriving. Johnson’s son says, “Dad, I think Nate needs you!” Nate’s throat has been cut, so he can’t scream.

Bystanders come to Leaton’s aid and call 911.

Johnson goes over to Hobbs, his friend and coworker, who is crumpled up, face down, near the top of the stairs. Johnson’s adrenaline is flowing; he’s keeping one eye on the basement door and another on Hobbs. He is still on the phone with 911.

“They’re telling me, ‘Try to see where the wound is.’” When Nate Hobbs rolls over, a deeper wound becomes evident, and “a pool of blood spills out of him, maybe a 40-ouncer of blood.” Amped up, Johnson considers going down to the basement, but 911 operators stop him, saying, “‘No, don’t go in. He’s still in there, and he’s on the phone with us.’”

Johnson tells other people to watch the perimeter, he says, as his mind races to make sense of the horrific scene and process his feelings of wanting to making sure that whoever did this doesn’t attack him while he’s tending to Hobbs, attack Johnson’s family, or get away. He decides he has to go down to the basement.

“So I go down, to go in, and [911 operators] stop me on the phone. It’s like, ‘No, don’t go in. He’s still in there, and he’s on the phone with us.’” Instead, Johnson stays “right next to” Nate “until they told me I couldn’t.”

Around this time, the hotel’s video cameras record a figure “emerging from the west side of the building where the back door of [Nelson’s apartment] and alleyway are located … [and] walking northbound away.”

At 3:48 p.m., a 911 call is made from Nelson’s number. The caller says he’s been “attacked by meth addicts in my basement,” who are in “really bad shape.” He says he’ll “turn himself in later.”

Police arrive at 3:49 p.m. and find Hobbs unmoving near the top of the stairs, Leaton in a ball in the middle of Davis Street. Paramedics arrive minutes later. Hobbs dies at the scene. Leaton dies at a nearby emergency room.

“Blood was located on inside and outside handle of Defendant’s back door,” a prosecutor’s memo says. Inside the basement was a “long-bladed knife on the ground and a sheath nearby.”

The Oregon State Medical Examiner’s post-mortems find that Leaton’s fatal wound was a “large gaping stab wound” which “penetrated Ms. Leaton’s chest cavity and right lung.” Hobbs’s throat was slashed, but the fatal wound was a stab wound “to the upper left shoulder that penetrated his chest and abdominal cavity … [and was] of such depth and force that it pierced Mr. Hobbs’s left lung, heart, right lung, and liver.” Both are ruled homicides.

In more than 200 homicide investigations and 13 years as a homicide detective, Detective Beniga testifies, “I’ve never seen a stab wound with that depth.” The knife police find is a blade “in excess of ten inches,” covered in blood, with long brown hairs attached. The basement is a horror show: “Blood-stained board, blood on the concrete floor, blood spatter, blood staining on the walls as well.”

Nelson’s phone is located the next day, abandoned a couple blocks to the north of the crime scene at Benson High School.

Police call in the U.S. Marshalls, and track Nelson’s unique purple mini bus. He is apprehended June 18 in the front passenger seat of a blue Mini Cooper, driven by a woman. “I know what this is about,” Nelson says when they grab him. The booking paperwork describes his housing status as “Transient – 4 Years,” and says he has no mental health diagnosis or medications. He has superficial cuts on two fingers, and a Band-Aid.

Hours later, after police clear the scene and everyone leaves, Michael Johnson goes down into the fourplex’s basement and turns the water valve to the building back on.

Outside of far-right media, which saw a chance to pin the murders on “antifa,” the murders of Hobbs and Leaton received little attention. “Portland writ it off,” Johnson says.

Nelson’s bail was denied, and he’s been incarcerated since his arrest. He pled not guilty to two counts of first-degree murder and requested a jury trial which has been postponed twice. That trial is currently scheduled for April 2024.

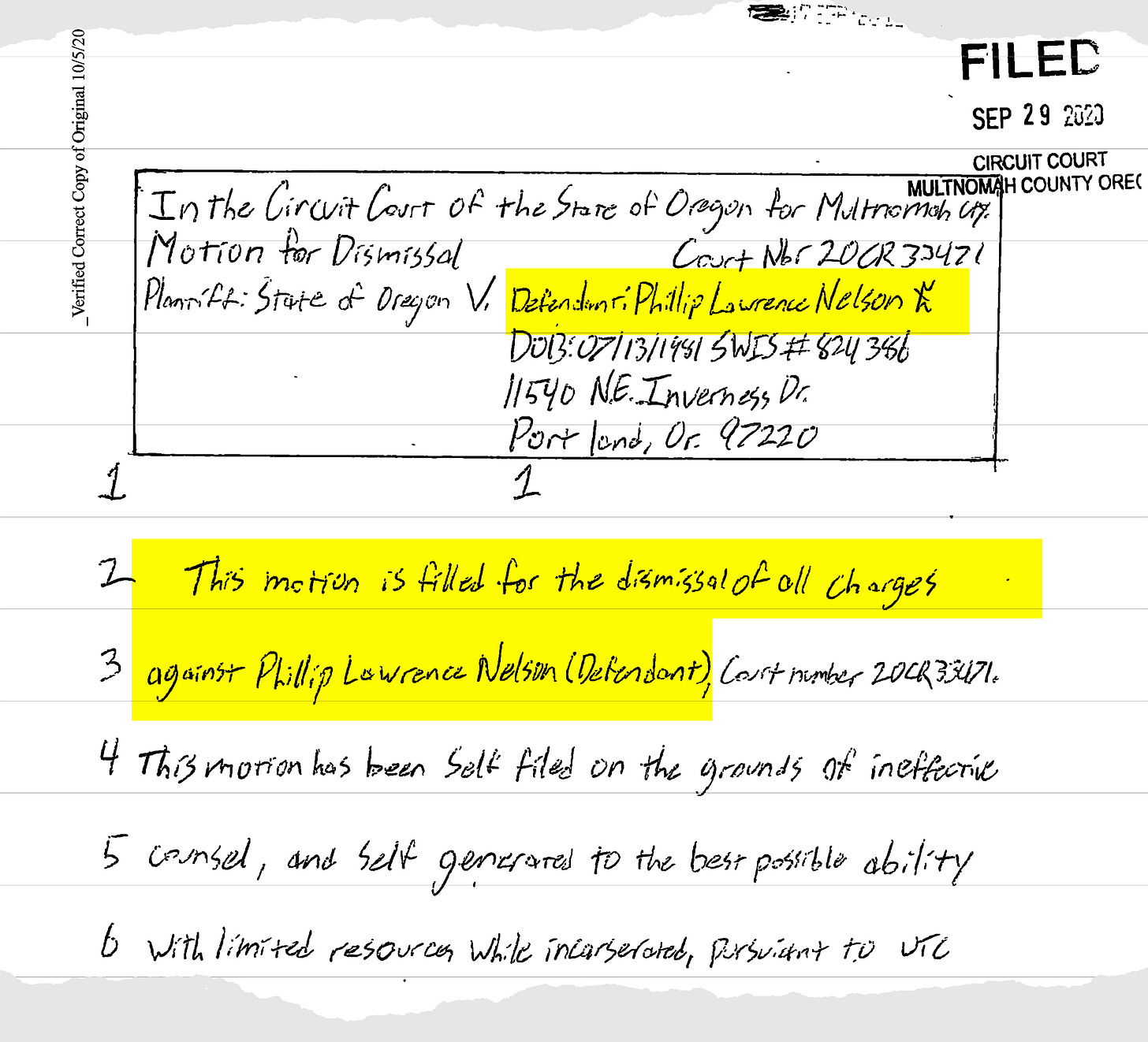

The wheels of justice have turned slowly, thanks in part to Nelson asking for and receiving a new attorney and requesting that the judge be recused due to a possible conflict of interest, which was granted. Nelson has also filed six handwritten lawsuits from jail, against the Portland Police Bureau and Chief Chuck Lovell, the Multnomah County Sheriffs, the State of Oregon, witness Michael Johnson — even Voodoo Doughnuts, the fourplex’s next-door neighbor.

One handwritten Motion for Dismissal Nelson filed in late 2020 asks for “the dismissal of all charges … on the grounds of ineffective counsel … the Constitution of the United States of America, Amendment VI, and the Constitution of the State of Oregon, Article I§10 … [and] the defendant’s right to a speedy trial [which] has been violated.”

In one 2022 court appearance, Nelson wore a jailhouse mohawk, dark circles under his eyes.

In his suit against the sheriffs, Nelson laid claim to a new identity. “I am Two Spirit,” Nelson wrote, using a Native American term that signifies a person with both masculine and feminine identities. “There is no shame of it in me … .”

The Hobbs family is not impressed. During one court date when the trial was rescheduled, Debe Hobbs says, Nelson wore “a grin on his face, [but] I felt like my heart had been ripped … I want justice for my son and for Cassy.”

The prosecution’s strategy in the coming trial can be inferred from arguments at the bail hearing. “On that day this terrible, terrible thing occurred,” Senior Deputy District Attorney Brian Davidson argued, “there was considerable, I guess, animosity going on in the apartment complex. Mr. Nelson had absolutely no right at all to be leasing apartments to people. We know that from the statements of the actual owner.”

“When the occupants, including Mr. Lee, Mr. Hobbs, Ms. Leaton and Mr. Johnson found out about it,” Davidson continues, “they confronted [Nelson], and it caused a considerable amount of tension. Understandably. The way that Mr. Nelson would retaliate against this was by going in the basement and turning off the water for the entire building, which caused a lot of angst for these folks, hardworking folks who worked at the bottling plant next door.”

After finding the Gatorade bottle outside his door, Davidson adds, Nelson decides “he is going to war … they go in the basement to turn the water back on, and with this war-like mindset, and this desire for retribution, he finds them in the basement, and butchers them.”

“Judge, I have been doing this for 20 years,” he added. “I have never seen a scene like this.”

For the defense, Phillip Nelson’s attorney Chris Clayhold told me in a phone call that his client “has a strong case, but I have to let the jury decide and hear the facts.” He declined to elaborate or respond to an emailed letter. Nelson, currently incarcerated at Multnomah County’s Inverness Jail, did not respond to a request for an interview.

Another of Nelson’s attorneys, Alicia Hercher, who no longer represents Nelson, admitted in the bail hearing that “there is direct evidence that Mr. Nelson stabbed these people, and that those stab wounds led to their deaths.” Damning as that may sound, Hercher’s overall strategy of trying to paint Hobbs and Leaton as “aggressive” meth users who were “mad,” and instigated the violent encounter by leaving a “bomb” in a Gatorade bottle, seems likely to form the basis for Clayhold’s upcoming defense.

The Leaton Family and Nate Hobbs’s mother, Debe, are both suing the estate of the fourplex’s owner. The Hobbs lawsuit “reflects the danger and injuries that can occur when, frankly, folks don’t take care of properties that they own,” Hobbs’s lawyer Peter Janci told me. “Ignoring these conditions is not just a private harm, you’re not just letting your property go to seed … you’re potentially creating a dangerous condition. We intend to argue to a jury that this was a foreseeable dangerous situation where someone put their interest in financial investment and earnings and holdings over the interests of our community, and two young people lost their lives because of that.”

Stover died on May 4, 2022. That same day, court records show, his stepdaughter tried to sell the fourplex for $250,000, according to a court filing by Debe Hobbs’ attorneys, which halted the sale. That’s far below its estimated value of $812,208.

Meanwhile, Hobbs’s and Leaton’s family and friends have been grieving and trying to heal. “This was not a way to die,” Nate’s ex-girlfriend Rhonda Durant said, part of a small group gathered outside the fourplex on Cassy’s birthday on November 1, 2021, to memorialize the couple. “They were both very caring people. … An addiction doesn’t make you a bad person, [just] lost.”

Debe Hobbs scraped together $14,000 to bury and plant a tree for Nate — a local native “Hogan” red cedar — plus a purple-and-pink rhododendron for Cassy at a Gresham park. She says she still struggles to sleep “because I picture my son being butchered to pieces.”

Michael Johnson mourns his neighbor, co-worker and friend Nate. “We used to get [up] at 4:30 in the morning and just sit there and talk and hang out before work started,” he told me. He wept as he bounced a baby on his lap in his living room. “So here’s this guy trying to better his life from the struggle of being homeless, he had been in prison, got out of prison, and I knew his struggle; that struggle’s hard. I had my struggles … but that’s hard too, you know? And you relate.” Despite his flaws, Hobbs, he says, was a “really good guy. Really. Good. Guy.”

Cassy’s friends poured their hearts into social media: “I miss u minnie mouse, I continuously look for u, and it breaks my heart to pieces when the reality hits,” one wrote, in a Facebook post shared by Cassy’s mom Nynette Leaton. “It’s 3am and I can’t sleep,” another posted. “Why can’t you come back?”

Debe Hobbs says one of Nate’s brothers has “never been the same.” Nate’s little sister Carmel has struggled. “Nate and I were like peanut butter and jelly,” she told me, between tears. “I fucking idolized him.”

Making sense of this wild, complex tale can be hard because of the ways this tragedy touches so many issues, from homelessness to political protest to the pandemic to landlord-tenant law, squatters’ rights, mental health and drug use.

Nationally, murders involving unhoused people have been spiking this decade, a trend I’ve written about for The Nation. Survivors all over the country have been left with wrenching questions like the one Cassy’s grandfather Randy Leaton asks: “Why did it happen at the point where they decided they wanted something better in life? That’s hard to accept.”

Also hard to accept: two of Hobbs’s and Leaton’s family members, when I interviewed them, were living in vehicles. Vehicle residency is the fastest-growing subset of homelessness, often missed by officials and institutions and a group we struggle to talk about.

Could anything have led to a different outcome for Cassy Leaton and Nate Hobbs?

Better building code enforcement, for one. Had the City of Portland forced Stover to fix up, or sell his fourplex, Nelson might never have rolled up and taken over.

Stable, affordable housing for Hobbs, Leaton, Nelson or Johnson, for another. As long as 16 million homes sit vacant, as Nelson told the cops, and affordable housing doesn’t meet the need, people like Nelson will keep breaking into empty nests. Mayhem may follow.

“Supportive” housing, which pairs subsidized housing with treatment, can be expensive — though not when compared with the societal costs of chronic homelessness — but many experts see it as best of all for people with multilayered needs like Hobbs, Leaton and Nelson.

Substance abuse or mental health treatment, even without affordable housing, can help people learn how to cope, forgive, grasp life less tightly. Maybe, with a sponsor, group, psychiatrist or other treatment option, Hobbs doesn’t fill that Gatorade bottle. Maybe if Nelson’s supports at the Veterans Affairs are there for him, he puts his huge knife away.

Here we come to conservative talking points, for had Oregon Democrats not shut down what seemed like everything, from housing offices to hiking trails to libraries, and moved many people from shelters to cots at the Oregon Convention Center, maybe this turns out differently.

Perhaps police resources also could have made a difference here. The Portland Police annual report for 2020 pointed to “critical” staffing shortages. On May 20 at the fourplex, presented with possible fraud, squatters and a simmering conflict, they made no arrests, issued no citations and apparently did not return for 27 days, until a double homicide.

Far-right media figures argued the blame lay with the decision to release Nelson after his arrest at the protest. But calls to lock up protesters and throw away the key are magical thinking, not good policy. Jailing protesters for long periods just for demonstrating is a violation of First Amendment rights, and local jails are too small to hold a thousand additional people anyway.

Finally, it’s possible a sterner response to Nelson’s domestic violence from Minnesota officials could have changed this sad story. Nelson’s crimes, which include throwing a pregnant woman out of a car and terrorizing small children, were enforced and prosecuted as a misdemeanor conviction for fifth-degree assault. He never finished a mandatory Batterer’s Intervention Program, choosing instead to just sit in jail.

So let a child’s words remind us that men who commit domestic violence are all too often punished lightly, then may go on to commit more serious crimes. This message was sent to Nate Hobbs’s family through an online fundraiser for funeral expenses:

“My name is [redacted]. I am sixteen years old. I need to somehow privately extend my condolences to this family. When I found out about this I cried for two days. Because my mother’s recurring, but ex-boyfriend is the man responsible here. I lived with him for about a year, my brother two, and it was the hardest thing I’ve ever been through. I can’t begin to imagine what the family is going through, but I want them to know they aren’t alone in the pain that that man caused. He destroyed my family and we are all suffering from it. I think everyday about what he has done, and what he has taken from us, and I am in such deep sorrow that he has done this to someone else. There is nothing that can right this, I cannot repent for anyone, but I am so sorry. I will pray for your family, and the lives lost, everyday for the rest of my life.”

Thacher Schmid is a writer, musician and former services worker. Follow: ThacherSchmid.com.

Chris Kim is an illustrator and cartoonist from Toronto, Canada.

Brendan Spiegel is Narratively’s Editorial Director and Co-Founder.

To subscribe to Narratively, click on this link. There are free and paid options (which allow you to listen to stories):